Flawed Pain Scales: What to Do When Emojis Fail to Describe Your Pain

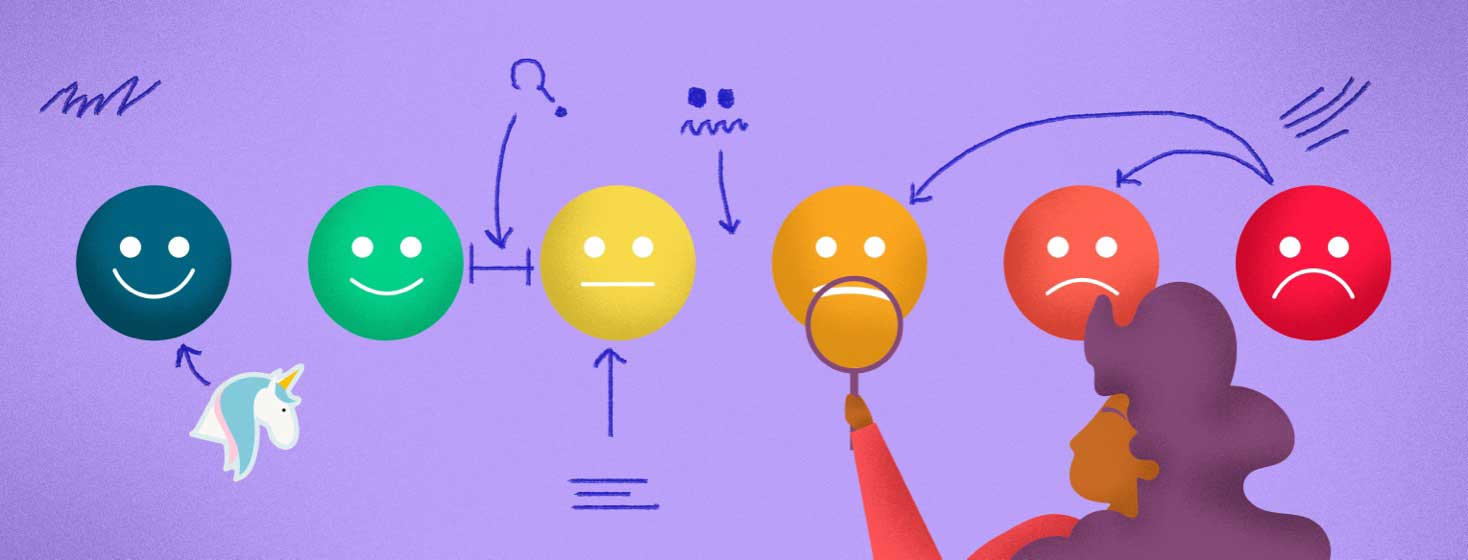

When I last visited the gynecologist, I waited for my doctor in the exam room. On the door, I saw a poster. "How are you feeling?" the sign read. It featured a line of numbers from 1 - 10.

Atop the 1, the sign depicted a beaming emoji. Above the 4, the emoji's smile had lowered into a straight line.

For the 8, the emoji had lowered eyebrows and a frown. For the 10, the emoji was crying.

At the start of my appointment, the doctor gestured to the sign. "Can you rate your pain on a scale of 1 to 10?" But numbers and emojis all fell short when I was trying to describe my symptoms accurately.

What is the FACES pain rating scale?

The sign in my doctor's office was the Wong–Baker FACES Pain Rating Scale. In 1983, Children's specialist Connie Baker paired up with pediatric nurse consultant Donna Wong to create a visual scale to help patients better articulate their pain.1

Baker and Wong created the scale specifically for children who might not have the vocabulary to discuss complex ideas of pain. For example, a toddler might tell the doctor, "My tummy hurts!" But if the doctor can gauge the severity of that pain, from "hurts a little bit" to "hurts the most," the doctor can anticipate the best treatment options for that child.

If a child has a more mild tummy ache, the doctor will react by prescribing an over-the-counter digestive medication. But if the child has severe abdominal pain, the doctor might encourage a CT scan to rule out dangerous conditions like appendicitis.

This famous pain scale helps bridge language gaps between a doctor and a patient. Yet a standard pain assessment cannot always account for people who regularly live with pain.

Tips for describing pain

Pain is subjective. I have become accustomed to daily discomfort. In the scheme of my chronic illness, how could I say that my version of a 4 might be someone else's 10?

If I said that I felt like a 4, how could I also emphasize that a 4 for me includes gnawing abdominal cramps versus the nauseating, incapacitating stabbing sensations that mark my 10: my routine endometriosis pains vs. a ruptured ovarian cyst?

Patients might consider using visuals to describe their symptoms. They might take a photograph of their pads or menstrual cups to show the color or texture changes in their blood flow.

They might show a schedule of their day during an endometriosis flare to demonstrate how their condition prevents them from completing important tasks. They might show their list of endometriosis care items to demonstrate the steps that they've already taken to cope.

A patient with endometriosis might benefit from using more specific language. It's important for a patient to advocate for themselves by explaining how they're feeling and how their symptoms are impacting their life.

For example, these types of phrases might help illustrate the scope of a person's pain:

- "For __ hours/days/weeks, I have felt (shooting, throbbing, aching, vice-like, stabbing, etc.) pains in __ part of my body."

- "These pains have prevented me from (getting out of bed, eating without feeling nausea, having sex, going to work, etc.)."

Some patients imagine new ways to revise common pain rating tools like the Wong–Baker FACES Pain Rating Scale. Are emojis and numbers helpful for you as you keep track of your symptoms?

Have you struggled to find the right words to tell other people about your pain? If you could redesign a pain scale, what might it look like?

Comment below to share your experiences and insights.

Join the conversation